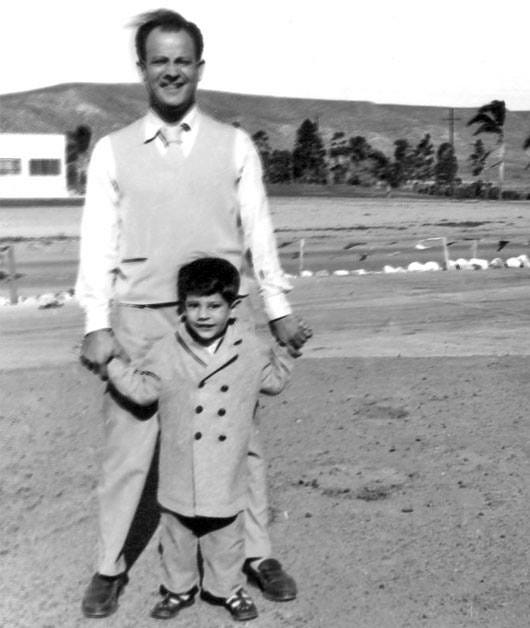

When I was four, my dad, whose clumsiness I inherited in spades, somehow bruised himself closing our garage door. A few days later, and I and were going to go somewhere together in the car, and a neighbor asked Dad about the bruise. Trying to be funny, Dad said I’d dropped the garage door on his head, and the neighbor gave me a tongue-in-cheek scolding that both he and Dad seemed to find very funny, but which mortified me. Why would my daddy accuse me of hurting him? It colored our relationship, with much more than a little help from Mom forever telling me that Daddy didn’t love me nearly as much as she did.

My parents were poorly matched in nearly every way, none more than in their public affect. At parties, my mother’s natural inclination was to find a wall to floralize, while my dad would go full-tilt hail-fellow-well-met. The life of the party, he. There are no photographs of him wearing a lampshade over his head, but I wouldn’t have bet against its having happened. And the more ebullient he became, the more intense my mother’s embarrassment. The morning after every social engagement would be hell on earth, as she would advise him implacably how mortified she’d been.

My dad’s son would grow up (to whatever extent I can be said to have grown up) wanting the Pope’s balcony, or at least universal fame ’n’ acclaim as a musician and actor or writer and graphic designer. Having lived through the Depression, Dad didn’t dare dream so boldly. He’d wanted to be a medical illustrator, and settled for doing God-knows-what at Hughes Aircraft for 30 years.

He pulled every string in sight to get me a summer job there as an expediter (whatever that was) when I was 19, for the princely hourly wage of $2, which meant that I was making a buck less, before taxes, at Hughes than I’d been making parking cars for eight hours at Ted’s Rancho or the Tonga Lei. As a parking attendant I got to listen to KHJ Boss Radio all evening, and — I will never, or at least seldom, lie to you — peek down the blouses of the shapely blonde dates I helped from their passenger seats. I resigned my commission at Hughes after two weeks, and it may have been the only time Dad was ever furious at me.

A few months later, I took a Greyhound bus up to San Mateo to see my girlfriend. Little wimp that I was, the son of a mother who’d inadvertently taught me from infancy that the world was full of menace and imminent catastrophe, I was pretty pleased with myself having managed the journey. I impulsively asked the driver of the homeward-bound bus headed for Santa Monica to let me out at Topanga Canyon Blvd so I could walk half a mile south, and then up the long hill feeling a real badass, singing the Rolling Stones’ “Going Home”.

When he returned home from waiting for me at the Greyhound station, Dad was understandably annoyed about having driven back and forth to Santa Monica for nothing. Rather than apologizing, I called him a bastard.

I was a teenager, feeling my oats. And today I am a regret-tormented old man living with the shame of having done so.

I understand now that I, historically an avid avoider of confrontations I was likely to lose (which is to say nearly all of them) did it because I knew my dad loved me enough to tolerate my being awful to him. (A little mitigation: he may have acceded to my being an unspeakable brat in larger part because he was a reflexive acceder to horrid treatment, as witness his having let my mother slash him to pieces verbally pretty much every day of their marriage.)

And then it got worse. Three years later, the young hotshot had been flown to New York City to schmooze a famous English pop group on behalf of its record company. I’d hung out with one of my idols, and almost become part of his band for one song at Fillmore East. I’d poached one of his groupies. There were fewer hotter shots in all christendom, and this particular one was too hot to do any more than grunt hello when his dad came to LAX to drive him home. Not a word.

Fast forward 22 years. Dad’s had a stroke that stole his ability to walk, and Mom, the queen of catastrophic expectations, has refused to allow him to come home to the house they’ve lived in for 31 years for fear that it’ll catch fire and she’ll be unable to drag him to safety. He is living in the malodorous “convalescent hospital” in which my grandmother died.

To my eternal discredit, I don’t insist that Mom “allow” him home. Instead, I take him around to a few nicer God’s waiting rooms. He declines all of them on the basis of their being more expensive.

We go to lunch. For some reason, he has decided to chew with his incisors. Because it’s not in him not to, he flirts up a storm with our young female server, embarrassing me beyond words. My needs of course take precedence over his, and I tell him to cut it the fuck out. God forbid I should allow him a bit of fun. (A little mitigation: the server was visibly discomfited.)

Dad shares a room with a mostly deaf and blind very old man. Back in Santa Rosa, I phone him one evening. Throughout my life, whenever he answered the phone at 3821 Castlerock Road, he would immediately pass it to my mother, either because he didn’t have much to say to me, or because she’d otherwise give him a very hard time. But not this time. His very old roommate, nearer the table with the phone on it, answers. I identify myself four times, each time a little bit more loudly, before he hears me. When he repeats, “Johnny?” Dad hears him and I hear him say, “It’s for me.” He tries in vain to get the very old man to pass him the phone, growing more anguished by the second. The phone never gets passed. I hang up without our speaking. Twenty-six years later, the memory of Dad’s franticness and frustration pretty well slices me in half.

He dies. Because…He Would Have Wanted It (even though the Mendelsohns of en-route-to-Malibu couldn’t have been less observant on a bet), Mom hires a rabbi who never spent a millisecond in my dad’s presence to come do a little memorial service, attended only by Mom, me, and my sibling. Sickened by the hypocrisy of Mom pretending to honor the memory for one for whom disdain she never tried to conceal her loathing, I gruffly refuse comment, and recognize now, all these years later, that my doing so was more about defying her than honoring my father in some (very) small way.

Gilbert Mendelsohn deserved a better son.

I composed these 10 songs about fascism late in the spring, never dreaming (or nightmaring) that the American electorate would later vote its principal American exponent back into the White House. A word to the wise: Learn a few in case those who don’t know ‘em put themselves in jeopardy of deportation.

This is well written and heart wrenching. So different from my childhood. I hope your daughter reads it. Sending love from Ecuador....

Dear heart. Much love 🤗🥰🖖